I went to my first gay bar when I was 15.

I didn’t go because I was gay, of course. I went because a friend identified as gay and they would let us in to drink, or at least that’s why my 15-year-old “I’m not gay!” brain told me.

The people at the bar knew better. They didn’t let us in because they believed we were 19 (the legal drinking age at the time). I mean, come on. I’ve seen pictures of myself when I was 15 and I looked 15. But they knew what was really going on and they let us in because in Cedar Rapids, Iowa in the early 1980s, there weren’t many safe havens for gay people. There was no internet or location dating apps. There were no gay-straight alliances in the local schools. There weren’t any positive representations of gay people on TV unless you count Paul Lynde.

The bar was the place where people could go and feel safe. It was a sanctuary. It was a refuge. Where you could be who you were, as feminine or as butch as you wanted to be, and dance and chat and be catty and gossip about who did what to whom and where or you could be serious and talk about the whisperings of some “gay disease” that was killing people in the big cities.

Even if the darkest of times – sometimes despite them – the gay bar was the only safe haven that existed for people like us, even if we didn’t recognize it at the time. The staff and the regulars protected us, especially when an older “chicken hawk” would try to move in on the young guys out on the dance floor. Inevitably, someone who worked there or one of the regulars would come over and chase them away so we could just have fun.

When I moved to California when I was 18, it wasn’t as easy to get into the bars, but I made it a few times. Long gone neighborhood places like the Apache, Job Site, and the Detour were usually easier than the big clubs in West Hollywood and they became my semi-regular haunts. I knew the bartenders and the DJs, and the doormen and they knew me. It was a great place to meet people. It was the only place to meet gay people.

When I turned 21 I got a job as a bouncer at a bar in West Hollywood. Over the next 15 years or so, I would graduate to bartender and then DJ, spinning in clubs all over town. The people I worked with became an extended family and while many of them, sadly, did not survive that particularly brutal era (the late 1980s especially), the ones that did are still special to me. I met one of my best friends there and we still go out to bars on occasion, although not as frequently and often with greater consequences the next morning.

Leaving at 2 or 3 in the morning sometimes made me a little unsettled. I didn’t always feel safe going to my car. But inside the bar was different. The angry, confusing, often hateful world stopped at the door and it was a relief.

No offense to straight people or their bars, but they aren’t the same. You may have a little neighborhood pub where “everybody knows your name” and you know theirs. The kind of place where they have your drink ready before you sit down, and they ask you how Mary or Bob is doing and commiserate with you about the grief your kids or your boss is giving you.

But it isn’t the same.

A gay bar is a safe harbor. It is a sanctuary. It is a refuge.

When the shooting at Pulse Nightclub in Orlando happened on June 12, 2016 it hit me hard. I was in Jamba Juice, getting my usual morning smoothie, and I checked the news while I was waiting. I read the story and burst into tears.

I knew that place.

I had never been to Pulse Nightclub in Orlando. I didn’t know any of the people who died or the people who survived. I didn’t know any of the first responders or the community leaders or anyone else directly affected by the shooting.

But I knew that place. I knew the people. I knew what it was like inside and I could practically hear the music and the laughter and the dizzying tumble of conversations. I could feel the pounding bass of the sound system and see the DJ’s head bopping along to the tempo and their patient smile when someone requested whatever song was the most popular for the tenth time that night. I could smell the cologne – people often wore too much of it in the clubs, probably to drown out the other smell, which everyone who has ever worked at a bar knows. It’s sort of a sickly-sweet smell, a little sour and yet clean, too, like bleach trying to remove a stain that just won’t quite go away. I could taste the drinks – they were strong. You always get a bigger pour at neighborhood spots. I could see the bartenders trying to keep up with the orders and trying not to let their annoyance show when someone ordered anything more complicated, and therefore time consuming, than a gin and tonic. I could see the smiles and feel the embraces and taste the kisses, from friends and from lovers and sometimes – a first time – from someone that you wanted to be one or the other. And most importantly I felt what it was like once you walked through the doors.

It felt safe. It felt like a sanctuary. It felt like a refuge.

Standing there today, looking through a pane of glass at a waterfall that has been installed on the side of the building I sort of felt like I could still hear the music and taste the drinks and feel the feeling of what it must have been like there that night, before it all went to hell.

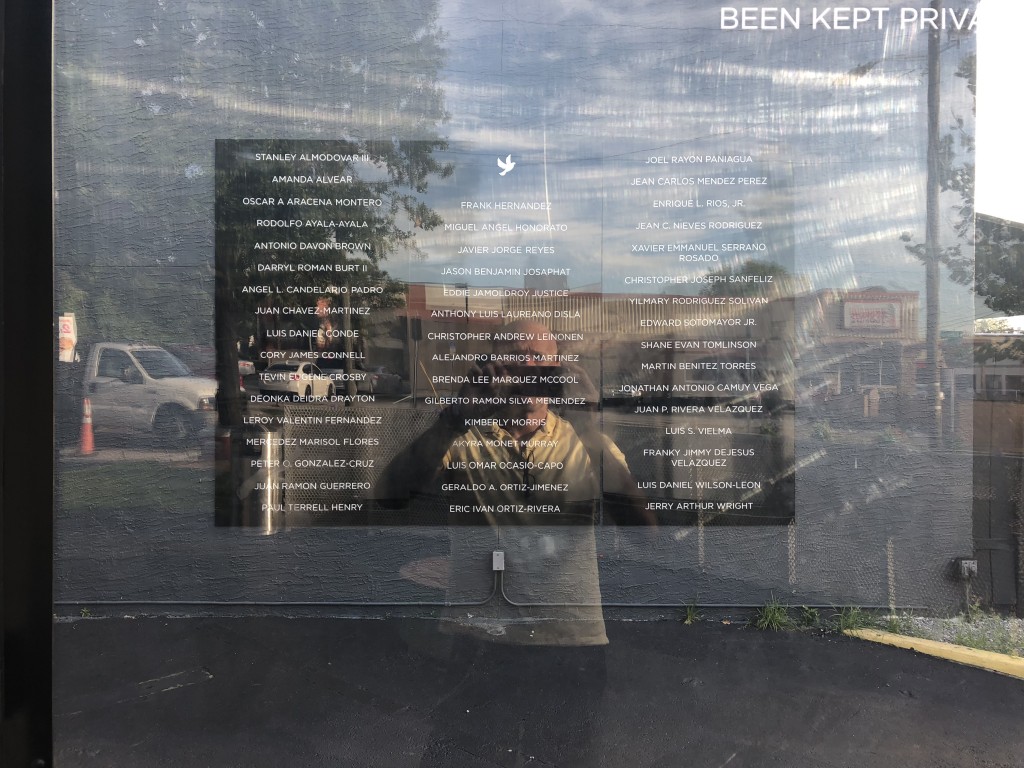

Then I looked through another pane of glass at the spot where the police used a battering ram to break through the wall, so people could escape the hail of gunfire. Then I looked through another and saw the names of the dead. The list went on… and on… and on…

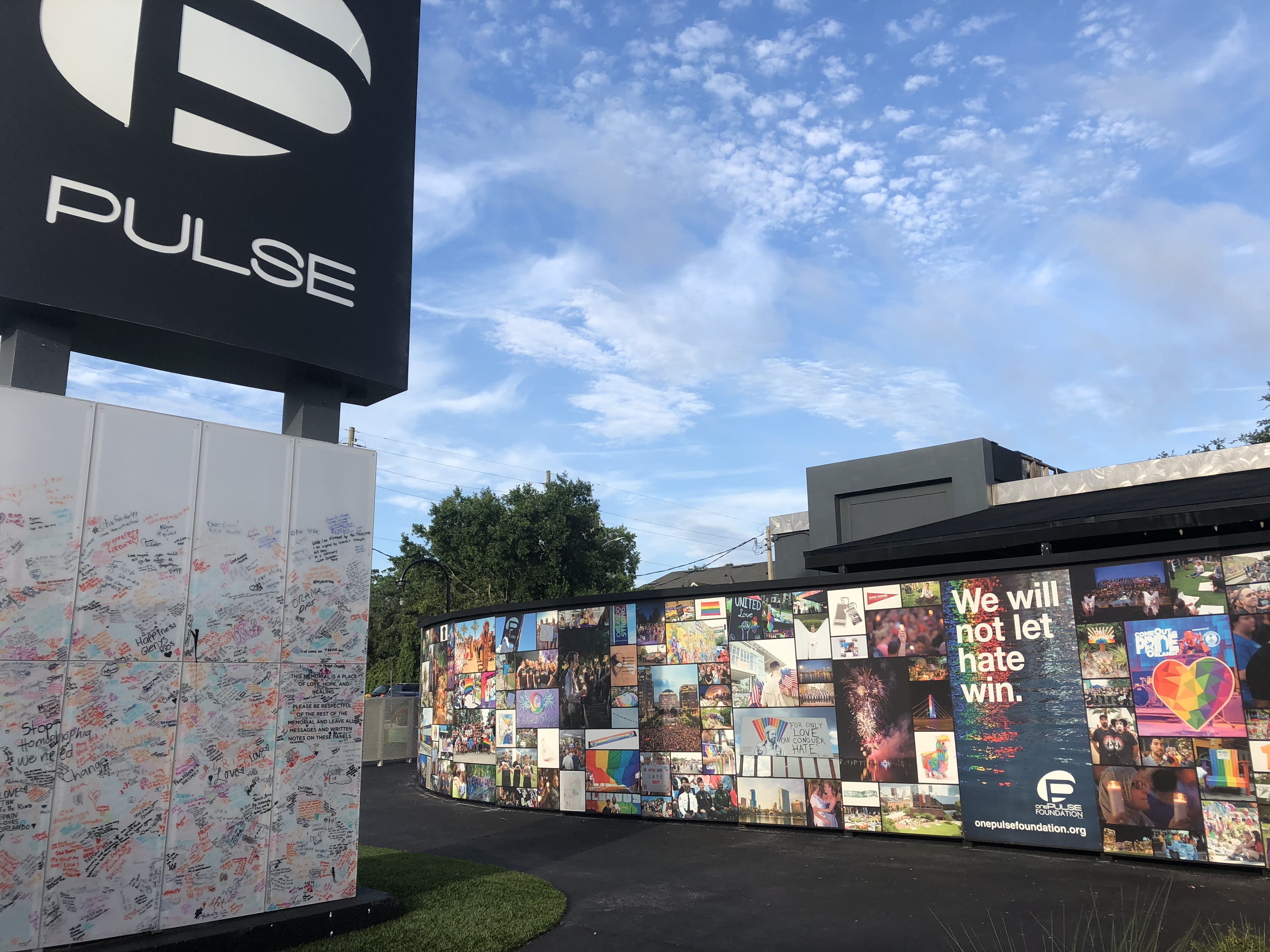

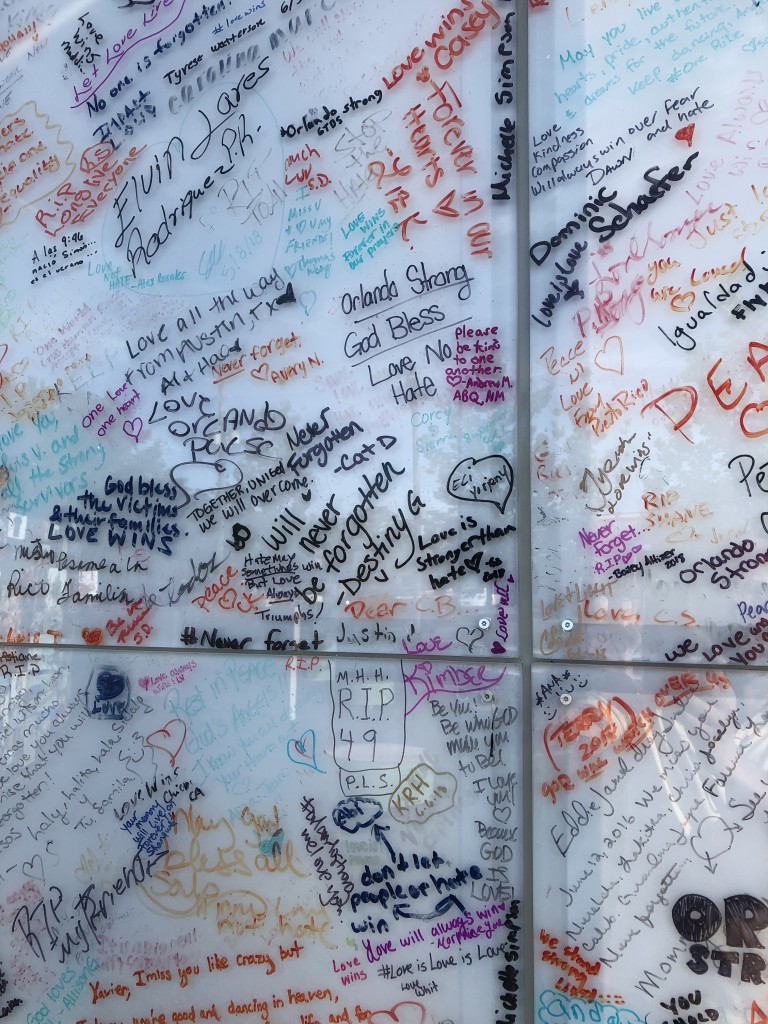

The interim memorial that is there today starts with a message board of translucent panels that wrap around the base of the sign out in front. On it people can write messages of hope, sadness, grief, consolation, or, in some cases I saw, just their name – a statement, I believe, that they paid witness to this hallowed ground.

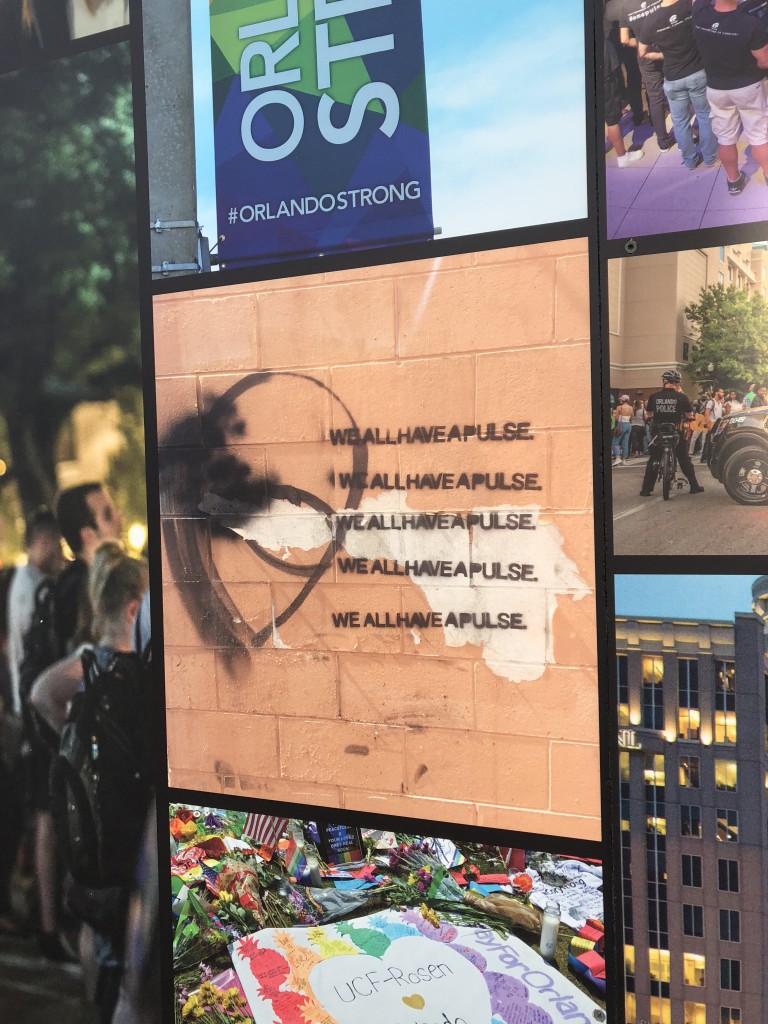

A tall wall has been put up around the building on three sides, covered with photographs sent in from around the globe. There are none of the night of the shooting. These are all of people coming together, mourning, grieving, and, ultimately, hoping and praying and taking action that will try to ensure something like this doesn’t happen again.

There are several windows in the wall allowing people to see the building itself, but they are done tastefully and always with an eye toward honoring those that lost their life – their names, the waterfall, the breach wall.

In front is a smaller fence that people can leave notes, photos, or tributes. All of them are collected and saved.

Finally, an electronic kiosk allows visitors to sign a guest book and learn more about the “Pulse 49.”

At first, I was a bothered by the rush of traffic whizzing by on the street a few feet away. Not only was it noisy, but it felt offensive somehow. “How dare you go on with your lives when something like this exists.” There should be a stop sign out front and everyone should be required to come to a complete halt, look at the place, and recognize its importance and only then will they be allowed to drive away.

But eventually that faded away and I could hear the music again.

The One Pulse Foundation was created by the owner of the club, Barbara Poma, to support construction and maintenance of the memorial, community grants to care for the survivors and victims’ families, endowed scholarships in the names of each of the 49 angels, educational programs to promote amity among all segments of society and, ultimately, a museum highlighting historic artifacts and stories from the tragedy.

The interim memorial was unveiled in the spring of 2018 and they are hoping to have the permanent facility finished by summer of 2020. They are currently working with the families, the community, and the local government to go through the design phase and are actively working on the capital campaign. They are negotiating to buy two adjacent lots, so it will take up a big chunk of a city block and are looking to places like the 9/11 Memorial and the Oklahoma City National Memorial as blueprints for what to do. This is not a government led effort – it is the owner of the bar putting together a world-class organization that is drawing support from everyone from major corporations like Disney to anyone who wants to contribute in whatever way, big or small, they can.

When I asked what I could do to help, other than write checks, I was asked to share my story since that was the most effective tool anyone has to create connections to tragedy.

I wasn’t there, but I knew that place.

For more information or to donate, please visit onepulsefoundation.org.

Please feel free to share this.

Recent Comments